Being a Writer Means Learning to Survive Platform Collapse

Late December is the time of year, I think, when people have the least interest in reading newsletters and I have the least time to write them, so let’s see out the year on a more personal note than usual.

I’ve gained a lot of subscribers this year and most of you have no idea who I actually am since the only reason you signed up for this is because I said something on Substack that you liked, or you thought I had the right politics, or I dissed an internet personality you also hate. Substack makes it so easy to subscribe that you can damn near do it accidentally, and statistically a large number of you haven’t read this far through the post. You gave up halfway through that long sentence I just typed and moved onto something else, because my sentences are very long, which is something I defensively call a stylistic choice rather than editorial malpractice.

Every week I churn out one of these and immediately lose ten subscribers who probably can’t remember subscribing and consider it an unexpected nuisance email.

So for those of you who are still reading, thank you and welcome. Today I’ll talk a little about myself, but I think you’ll get something helpful out of the conversation as well. Particularly if you are a creative who relies on this platform, or any platform, to get eyes on your work.

Two years ago I started writing a novel. The plan at the time was that it would be finished by now but I’m still chugging away at it. Changing my mind, revising parts, and sometimes letting it sit untouched for months at a time. I’m okay with this because it’s not a Dead Book. It’s a pretty good idea for a book, I think, and I still feel good about the odds that I’ll finish it. The problem always was that I wouldn’t know what to do with the book once I did finish it. There are no publishers who will accept an unsolicited manuscript and there are no agents who will work with my genre. I didn’t want to self-publish so I was kind of stuck.

I did find a small local publisher that was growing in size and reputation called Shawline. They took unsolicited manuscripts, they published genre fiction, and they’d even started opening their own chain of bookstores.

I am a realist and I didn’t start planning my book tour or anything, but the existence a place like that, which just might give a shot to a guy like me, was a strong motivator. I bookmarked their website while I worked on my book and every so often I’d scroll through their catalogue and buy one of their releases. I knew it would take hard work but I was confident that Shawline, or something like it, would be there for me once I eventually cranked this thing out.

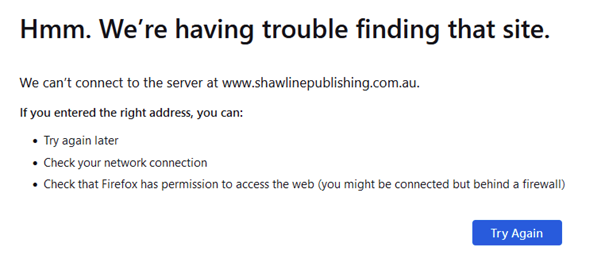

So just the other day I clicked on that bookmark to see what the latest is on this promising little publishing house that I hoped would carry my book one day.

Website was down. Okay, so I hit Google to see if I could find anyth—

Now, you can put a positive spin on this: If I hadn’t dragged my feet on this book then I would probably be in a fetal position right now. I never followed through with my plans to send them a manuscript and so I haven’t wasted the past couple of years putting together a book that I can’t sell because the rights to it are held by some liquidation company that might sit on it for years while they figure out if they can turn it back into money somehow.

Shawline, it turns out, had been in a failing business tailspin for some time and was really good at hiding it. Its CEO was living and operating under a nom-de-plume to hide the fact that he had a string of failed businesses and a criminal history. This wasn’t just a start-up that came into hard times, it was already a time bomb from before I even discovered it some years ago.

Still, since the beginning of this year some doubts had bubbled up from the subregions of my conscience about whether I actually would wind up approaching Shawline. It was, after all, a hybrid publisher. That means the author lays down some of the cost. I’m not a fool, I know that screams vanity press, but I also know that it’s not necessarily a scam. I’ve seen a lot of vanity presses and I know what to look out for. This was an exceedingly professional-looking operation that had been serving a number of authors quite well for years.

There was still this tiny little voice whispering this company is going to collapse.

It was enough that I actually remember Googling for what happens to an author’s intellectual property if their publisher goes out of business? (If you’re wondering—it depends on what’s in the contract, and I’m even more comforted knowing I don’t think I would have signed this one). I can breathe easy that I avoided a really bad decision here even if it means I’m stuck in a cottage industry of Australian publishing houses who won’t touch any fiction that isn’t about three generations of an immigrant family dealing with prejudice in contemporary inner Sydney.

I realise now that I had two little beasties fighting inside my brain and one of them was that rat bastard called Good Sense Earned Through Years Of Experience, trying to drown out the sweet, comforting voice of Hope.

I needed that hope and there’s a reason it nearly got the better of me. As recently as 2018 I was making good money as a writer and editor for the pop culture website Cracked. It was the best job I’ve ever fucked up, and boy did I fuck it up. I wasn’t one of their celebrity writers so I didn’t get the benefit of my name splashed across the website and I spent ten years—ten years!!—doing zero self-promotion.

One of the reasons I didn’t do social media that much was because I couldn’t effectively do short-form commentary like tweeting. I’m still not great at it. Your boy just doesn’t know how to post. But another reason was that I kind of just assumed that Cracked, or something like it, would be around forever.

I’ve written before about the online media collapse of the mid-20teens and my longtime readers are probably sick of hearing about it but it really was my villain origin story. The vat of acid that the techbro billionaire class threw me into. There were multiple reasons for it but chief among them the decision by Facebook to extort the entire media landscape by suddenly demanding payment for the simple act of sharing a link.

The free movement of people around the internet had been the backbone of the entire economy of the web up until now. It’s hard to believe given how deeply ingrained and entrenched the internet is in our lives today, but it was really only good for around 20 years. I am measuring the Good History of the internet between the years 1995-2015. If you were born in 1995, then in less time than it took you to reach college, the internet as an arena for creative expression was born, thrived, and then murdered at the hands of Mark Zuckerberg.

Cracked itself existed as a really good website for just under half of the best age of the internet, but that was enough time for many of the staff who were smart enough to promote themselves to transition into successful writers and podcasters once the website fired all of its staff in 2017 and transitioned into a site that now just posts screenshots from Reddit. I didn’t even have an active Twitter account when Cracked ended. What I now think of as the First Collapse in my writing career reset it right back to zero at an age where zero is absolutely not where you want to be.

One of the reasons I think Stephen King is so successful is that he existed in the exact, precise, perfect window of time for a publishing genre author. I mean, he’s just a great writer, one of my favourites, but it’s also an accident of history that he is so huge. He hit the sweet spot in the 70s and 80s for the type of writing that he does. I legitimately hope that he lives and writes for another 20 years, but he will never need to struggle again the way he struggled before Carrie. His body of work will be behind him before the last bookstore on Earth becomes a Spirit Halloween. He might still live to see that, though.

The institution that made King successful was an institution that lasted his whole life, but collapses happen much more frequently now. There’s a certain quickening. The collapse of Cracked was also the collapse of everything like Cracked. I had to write, it was the only thing I could do, but the channels of transition for orphaned internet writers were either podcasts or TikTok.

Or I could play on hard mode, start a solo blog, and try to learn how to do social media.

To my surprise, I actually started to get pretty good at Twitter. I hadn’t used my account anywhere near as much as I should have the whole time I was working with Cracked, but it was enough that I did have a small number of blue check users following me, which at that time actually meant something, and I figured out that there was an actual, learnable, art to the viral tweet. If I could time things just right, then I could tweet the kind of thing a blue check was likely to retweet. If they did, then I had a good chance of going viral, and there was a way to then hijack your own viral tweet to link to your blog and watch subscribers flow in.

That was actually really fun for a year or so. It felt like a strategy game, which put some thrill into the slow process of rebooting my writing career.

Then Elon Musk came along and murdered Twitter. And that was that.

What we as creatives on the internet are left with, now, is this constant churn of platform collapses caused by a combination of shithead tech startup idiots who ruin everything they touch like it’s a sport, and panicky governments who also break everything because they’re either trying to help, or protect against, the tech idiots.

Some of my former Cracked colleagues who picked up the pieces by learning how to TikTok are now looking down the barrel of that entire platform being banned in America, and I have no idea what they’re going to do. Here in Australia they’re going to ban all social media for people under 16 next year, and there’s a similar law called KOSA being proposed in America, both of which will likely force draconian surveillance and anti-anonymity measures that will reshape social media in ways we can’t even imagine yet.

This is an absolutely exhausting time to be a writer.

Look, I’m going to find some way to write no matter what happens. You can chop my fucking fingers off and I’ll type with my nose. I am completely finished, however, with trusting platforms and relying on any specific model of promotion to stick around longer than a year. That’s why I’m now investing quite a bit of my efforts into supporting platform decentralisation wherever I can.

So what advice do I have for you, if you’re another creative trying to navigate this minefield? Well, if you’re another Substack writer, then my advice isn’t going to be pleasant but I really think you need to hear it and take it seriously:

I now believe Substack is going to collapse.

I wrote again about my frustrations with the platform a couple of weeks ago but having thought longer about it I don’t think I was hard enough on it, especially knowing now what I know about Shawline and seeing so much rhyme in it.

I wasn’t following the Shawline mess in the months leading up to its implosion but evidently the unhinged CEO became progressively less hinged as time went on and the walls began closing in. In comparison, it’s difficult to tell whether Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie is becoming more insufferably patronizing over time or whether he troughs and crests.

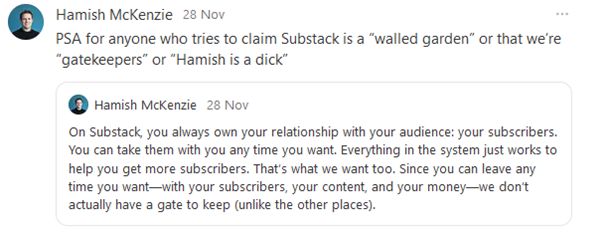

In any case the relentless and very obvious ways in which they’re trying to lock writers and readers inside of their app, boarding up the walled garden while repeatedly and insultingly insisting that it isn’t one reaches heights of skeptical eyebrow-raising not seen since the sixteenth time Joe Biden insisted he wasn’t going to pardon his son.

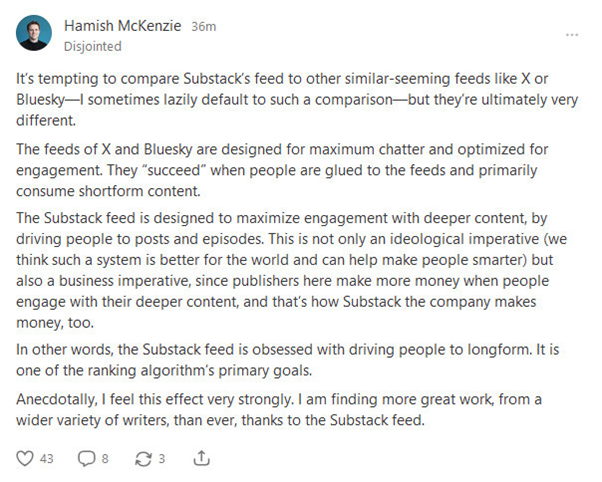

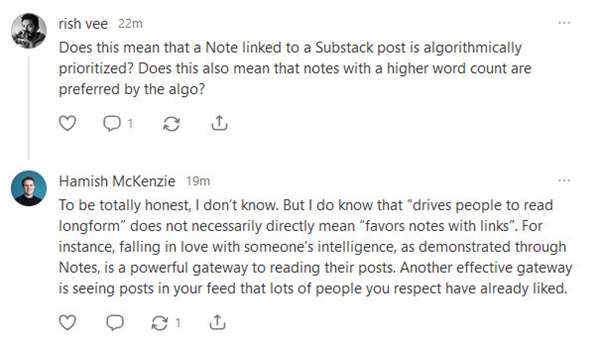

When I detect gaslighting I start checking the exits, because I’ve been through this too many times now. And there’s plenty of that going on at Substack. Here’s Hamish talking about how Substack’s internal social media network simply cannot be compared to similar looking platforms like Twitter or Bluesky because it's "designed to maximise engagement with deeper content."

But when pressed to explain how it's designed differently he replies "I don't know."

Look, Substack is a venture capital backed startup whose owners are about to start trying to gaslight you into thinking venture capital is Good Actually. And they’re going to do this because they’re entering the phase where they will have to enshittify to survive.

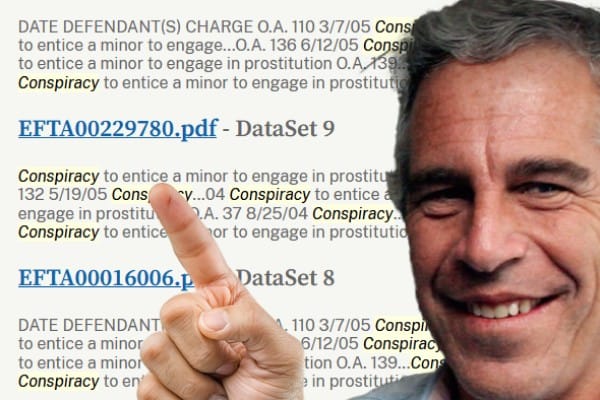

Substack’s primary venture funding comes from the same circus of evil clowns that’s trying to engineer every platform on the internet toward Peter Theil’s bizarre fucking space monarchy nightmare future, and the numbers just don’t add up.

Venture capital firms typically expect a 10 time return on their investment within 5 years. Andreessen-Horowitz, Substack’s primary source of funding, the firm chaired by this fuckwit:

…has pumped around 70-80 million dollars into Substack, meaning that Substack is likely on the hook for an astounding $800 million in returns over the next few years. And how much does Substack actually make with its business model of slicing 10% out of every writer’s income? It’s currently less than $800 million. Hoooo-BOY is it ever less than $800 million.

My expectation is that I might need to change platforms in 2025. Maybe. All of my readers will be in the loop well before I decide to do so and it’s absolutely in my interest to make it as seamless as possible so maybe you’ll hardly even notice. But for my fellow Substack writers, some advice: Do what I’m doing and, at the very least, back up your subscriber list regularly. Being a writer on the internet in the 21st century means keeping your bags packed.