Real Time True Crime: The Unsatisfying and Often Damaging Outcomes of Internet Sleuthing

Within an hour of Luigi Mangione’s name being released, the whole world was scouring his biography. What people found didn’t make the kind of sense they thought it would.

A wealthy heir to an Italian-American real estate fortune, Mangione looked up to figures as diverse as Sam Harris, Nate Silver, and Peter Theil. He did suffer from a chronic illness, as many had suspected given his target, but he hadn’t been affiliated with that particular insurance company or been in a position to be unable to afford treatment.

We still don’t know in his own words, exactly, what Luigi Mangione wanted. He caught with a 260 word note that the media is calling a manifesto and which I’m not completely convinced is real because it seems too on the nose, but I’m not an outright skeptic. Because none of this makes perfect sense, or even a comfortable amount of it.

But we know what we know, and we knew so quickly, because of Mangione’s extensive social media footprint. He was highly literate, a voracious reader, and engaged frequently online. They found his Twitter account. They found his Goodreads account. They found his Substack account—a user account only. Luigi did not write a Substack. Until he finally made his statement—and what a statement it was—he was a reader. We know him mainly from what he chose to take in.

What we did learn mostly just confused us.

Everyone wanted him to be a Bernie supporter, essentially. Or at least, that is the furthest to the right and to the mainstream politic he could have been to satisfy the perfect narrative. For those who celebrated his deed, he was supposed to be their passionate thought leader, their champion against predatory capital, the permission that the people needed to declare enough was enough. For those who opposed him, it was also desirable for him to be a left wing radical. To go mask off, to show the normies what these people are really like.

In the hours after Mangione’s identity was revealed, the journalist and manager of the Cool Zone Media podcast network, Robert Evans, wrote one of his most comprehensive and detailed biographies. He does not appear to have been a strong ideologue of any sort. How do you categorise someone who has expressed appreciation for both Elon Musk and the Unabomber? The crime was not random, this much is clear, but could you call it political? He may have been radicalised by pain, but t was not the end point of any consistent or coherent ideology.

But then, of course, how much can we really confidently say about the man before he opens his mouth?

We are living in an era unlike any before it. Increasingly, when some total nobody commits a crime that launches them spectacularly into the public eye, we have immediate and direct access to enough primary sources that we can piece these people’s entire story together. Or, that we think we can.

We can go down this rabbit hole with Luigi pretty far as more of his online activity comes to light. We can take forking paths. He was a big fan and paying subscriber to a Substack author named Gurwinder Bhogal, who in turn was a former member of a right wing QAnon-adjacent think tank called Quilliam, and with whom he discussed alt-right coded ideas, like frustration that people acted like NPCs. I don’t mean to mention this as a means of cancelling Luigi Mangione. On the contrary, I mean to highlight how complex this is.

Much has been said about the popularity of the true crime genre, but thanks to social media we’ve transitioned into the era of real time true crime. As recently as the Parkland school shooting in 2018, it would take days for forensic experts to assemble a portrait of the killer’s mindset and for this to trickle into the media.

Now, when a gunman opens fire, you can have a true crime podcast in production that same day, that same hour.

The natural result of this new information landscape is that the scramble for information has turned into a speed race, and the competition is between those who want to craft a true narrative, and those who want to craft a preferred narrative.

On the 16th of December a school shooter opened fire in Madison, Wisconsin. Within minutes, people were scouring social media for the identity of the killer, for the accounts they knew would be there. Young people all have accounts. The only question was whether this person was a Twitterer or an Instagrammer. Somebody out there knew who this was. They would find the tweets.

There’s a certain type of personality on the internet who lives for this shit. The hunt. The crimefighters. No longer relegated to trying to solve cold cases, these cases are red hot and it doesn’t matter whether the perp is on the run or dead, the important thing is beating the cops and the media to the identity and the motive. Rush across the finish line, take the prize.

In this case, though, some of the amateur sleuths were driven by an additional motive—to find evidence that the shooter was part of a marginalised group they sought to further marginalise. With spree killings this has become as predictable as American gun violence itself. The Elon Musk Right, the LibsOfTiktok crowd, hunt down evidence that the shooter was transgender, nonbinary, or otherwise queer, with all the ferocity of Trump demanding they find him more votes in Georgia.

If they can’t find this evidence, then it’s good enough to manufacture it.

It was quickly enough reported that the Madison shooter was a girl. Female spree killers are incredibly rare. This gave powerful hope to reactionary sleuths who wanted to prove that the shooter was in fact a “biological male” who identified as trans. When photos began to circulate it was prime time to begin analysing hand ratios and facial bone structure.

But the transgender narrative kept falling apart as quickly as it could be built. Once they pinned down the likely suspect, once they had a name and a photo, the narrative builders began slurping up evidence and worldbuilding anew. The likely killer was 15 year old Samantha Rupnow. There was, floating around, something that might be called a manifesto or maybe just an extended Discord rant.

From this evidence, two simultaneous competing narratives were built. The one preferred by the Trump crowd and pushed by Chaya Raichik, short list contender for the dumbest human being to own a computer, was that Rupnow was a radical left feminist so poisoned by her hatred of men and her love of socialism that she was driven to directionless bloodlust.

The alternative narrative pushed by the left was that she was a neo-Nazi who was embedded in the Nick Fuentes fan circle and radicalized by far right white supremacy.

The true story, as close as we can get to one, is very oddly kind of both.

The entire story I just told took place the same day as the shooting itself. We watched it unfold in real time as internet sleuths rapidly dug up evidence and attempted to mould simple narratives from it, score points for one side or the other. A day later another postmortem of the whole mess landed on Robert Evans’ publication (researched and authored this time by a colleague).

The reality was much more complicated than anyone wanted it to be. The killer’s motives couldn’t neatly be situated politically in a way that could enable anyone to place her in one camp or the other. She wasn’t transgender or queer. She was female, but she was strongly associated with the deeply misogynist “incel” subculture. The abundance of information kills her utility as a symptom of any one thing. Her screeds expressed a twisted caricature of radical feminism that crossed into misandry but she also made ample use of the N word and praised Hitler, and what are we supposed to do with that? How are we supposed to use that?

Science fiction has frequently flirted with this familiar trope that we will one day upload our consciousness into computers, and in a way that’s kind of happening but not in a way that features and cool Lawnmower Man shit. The hundreds of millions of people who now use some sort of social media are essentially uploading some percentage of their personality into the public cloud.

That is frightening. It allows no real room for growth. Anything you say online is a matter of public record, frozen in time capsules. If you say something so embarrassing at work that it hangs over your head then you can always just get a new job and start afresh, but not if you say something shitty on the internet. That becomes part of your whole person forever. And it’s not just your words, either—your search history, your voter registration, and how you spend your money is now etched in obsidian.

It’s hard to spin that positively. It’s a dystopian concept that we’re living. If I can, though, venture one possible upside, it’s that it allows us to actually see the complexity of the individual and the humanity of strangers. It breaks narratives that people are perfectly simple products of their environment.

This was clear both of the occasions someone took a shot at Donald Trump during his 2024 campaign. Naturally, the desired narrative about Thomas Matthew Crooks would be that he was a radical leftist deranged by Trump hatred, and that was of course the first claim that Trump’s supporters leaped to.

But Crooks’ online record defies any simple characterisation. He was only 20 years old. At some point it appears he did donate money to some liberal organisations. But he was registered Republican at the time of his death and his social media of choice was Gab, the neo-Nazi Twitter clone, on which he was known as a bit of a, well, a neo-Nazi. Attempts to dig up any evidence that he was some kind of hardcore Biden fan only painted an ever clearer picture of him as the sort of guy who would vote for Trump twice if he could.

And yet, he tried to kill the man. Why?

We’ll never know. Crooks is extremely dead. He hadn’t had a chance to build much of an online life and what little evidence we have produces only a frustratingly counterintuitive narrative.

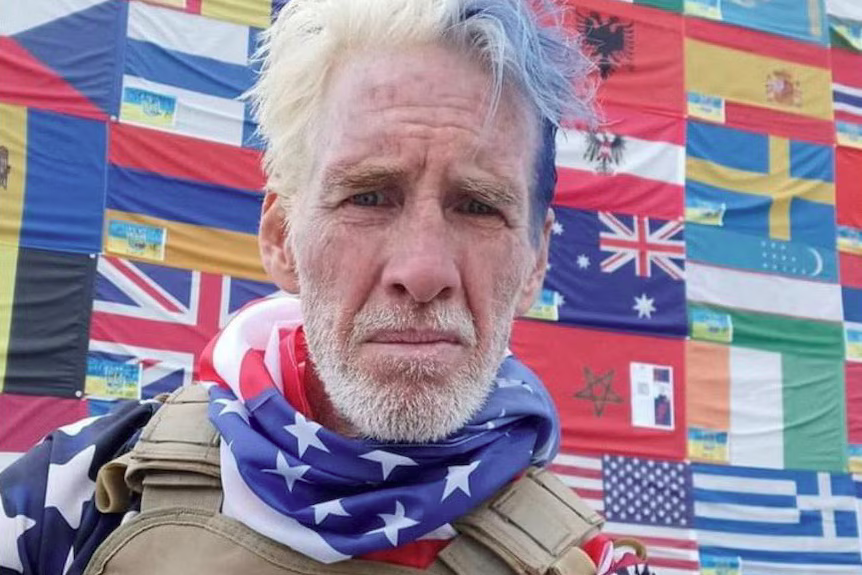

A better candidate for a clean anti-Trump narrative seemed like the second would-be assassin, Ryan Routh, who snuck into Trump’s golf resort with a rifle but was caught before he could squeeze off a shot, if that was his intention. Routh, convenient for the purposes of narrative-building, was a diehard Ukraine supporter, the kind of cookie cutter liberal you’d see with sunflower emojis and flags in his social media profiles.

But he was more than just your regular NAFO-bleating lib. He travelled to Ukraine in the hope of actually joining their military as a volunteer, but was rejected for coming off as a nutcase. But he was loud and active on social media, which set off the usual race in the hours immediately following his identification.

Again, both sides of politics thought they had enough useful material to pin him as an easy fit for the favoured narrative, but again, the more dirt the sleuths dug up on the guy the less coherent the image of Routh became: He was a Trump supporter. Then he disavowed Trump and supported Bernie Sanders against Biden. Then he pivoted right again and supported Tulsi Gabbard, before going all in on a Nikki Haley ticket, then preferring Ramaswamy. All of the time he was backing Republicans for the presidency he was donating monetarily to the Democrats. His voter registration flipped wildly over the years between Democrat, Republican, and Independent.

You might want to call him a hardcore centrist, but not in the sense that he was aiming for the centre, but more in the sense that if you throw a hundred darts roughly and randomly at a dartboard and take the average it will round toward the centre.

Those who sleuth the internet for clues in the aftermath of a crime think that they are digging up puzzle pieces, but contrary to expectation, they regularly find that the pieces don’t fit together and the more they assemble it the less it resembles the image on the front of the box.

During that initial frenzy, of course, the information zone gets flooded with total bullshit, either as a result of deliberate narrative building (like the desperate need to prove every killer is transgender) or just flat carelessness.

In 2009, an Iranian university academic, Neda Soltani, had to flee for her life in the days following the public murder by the Iranian Police of a different woman with a similar name, because internet sleuths with absolutely terrible face recognition skills homed in on Soltani’s Facebook profile. The ensuing media frenzy around the still-living Soltani caused endless confusion and conspiratorial false-flag slinging around a woman who was supposed to be dead.

And nobody should forget, of course, the ultimate notorious example of internet vigilantism gone horribly wrong: The Reddit-wide hunt for the Boston Marathon bomber that turned into a media frenzy as dozens of sleuths thought they’d pegged the missing Indian-American university student Sunil Tripathi as the killer based on piles of spurious evidence they maniacally concocted in the hours after the deadly attack. The mixup triggered a nationwide witch hunt and demonization of the innocent student who, it turned out, was only missing because he’d secretly taken his own life before the tragedy even happened, and had nothing whatsoever to do with it. Reddit, the website, had to issue an apology for the reputational damage caused by its idiot users.

What’s important to take away from all this is that, even though this kind of bullshit happens each and every time a major crime is committed, it never works out the way that anyone expects. Three things are always certain:

The initial information is always wrong; the correct information, once revealed, disagrees with expectations; and the truth either teaches us very little or nothing.

One thing is pretty consistent: The more extreme the crime, the more likely that its perpetrator’s motivation is either irrational to a degree we cannot understand, or complex to a degree that we cannot penetrate. Maybe in the coming months the saga of Luigi Mangione’s ongoing discovery and trial will reveal truths more lucid and exciting than is common with these sorts of things, but I suspect it will wind up more unanswered questions than we started with. True humanity remains, as always, complicated.