Relax, You'll Never Make a Living on Substack

As well as general politics and pop culture I like to write about the goings-on of social media, and this week's piece is about Substack Notes. As subscribers to the Ghost version of my newsletter, you might have no idea what I'm talking about. If you're interested, though, I’ll explain a little bit about what Notes is.

Substack has all sorts of ways of spinning it to make it sound groundbreaking but when you get down to the brass tacks it’s a Twitter clone strapped to the front end of the Substack app and website that forms sort of a dual community hub and discovery layer. It’s quite ingenious, actually, in the kind of evil way that most platforms try to trap your attention—it mimics the way that social media is used to discover and share blogs, but the blogs are nested within the Notes environment itself so that you’re never actually leaving the website or app when you click on something, ensuring everything remains inside the walled garden.

As a general rule, though, the Notes “community,” in so far as there is such a thing, are kind of loathe to see it as something so banal as social media because they are writers, not influencers or anything of that sort. It’s a cozy literary hub, not a lowbrow den of memes and politics and Nazis. And I can’t stress that enough, don’t you dare say there are Nazis, there are no Nazis, ain’t now and never were. Subtack folks get really upset by that allegation for reasons we’re not going to get into!

I do like Notes. I like a lot of the people there and I like hanging out there (not least because it’s the only social media platform where I get any engagement) but the community at large tends to labour under some illusions regarding Substack as a whole enterprise. You can’t blame them, the illusions are planted deliberately by the guys who run the site, it’s the entire strategy. It’s one of the most popular illusions in the history of humankind—that you’re eventually going to make money doing this.

Like other social media the site has its own checkmark system but rather than based on notability it’s based on revenue. It’s something to chase. Instead of three different coloured ticks it should be three sizes of money bags attached to a fishing pole. It’s an advertisement to other users that you made it and so can they.

“We don’t make money unless you make money!!” is one of the oft repeated slogans they bat around every time someone accuses the admins of giving someone-or-other a rough deal.

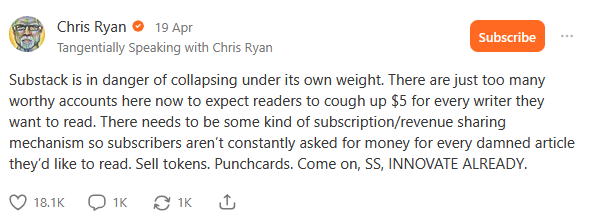

Two recent rounds of discourse on Notes have led me to realise that this illusion is much more widespread and ingrained than I’d even known. One is a familiar topic that resurfaces now and then about people wanting some kind of revenue sharing model so that more writers can get paid…

…and the second was the short-lived arrival of bestselling author Glennon Doyle, who signed up for the platform and was immediately bullied off—No, scratch that—as my critics insist I word it: Voluntarily chose to chicken out of using the platform after being unable to hack a very large but fair amount of valid criticism of a successful and presumably already wealthy writer joining an indie platform and earning an amount of money she doesn’t need but we do.

In any case, I feel like it’s time for another possibly ill-advised episode of S Peter Davis Shits Where He Eats, but one that might relieve some people of the anxiety of chasing that orange tick:

Either zero, or a number that can be rounded down to zero, of the people reading this will ever make a living from Substack. Some of you might eventually make a living writing—that’s still my goal!—but you won’t do it here. Because…

Think of the numbers involved

Here’s a funny thing about those checkmarks, right—there’s three tiers: Hollow orange, solid orange, and blue. These are, again, little tokens for you to chase, but they scale up exponentially, not linearly, and so the numbers go from trivial to utterly insane in—well, three steps.

Hollow checkmarks look super fancy but they aren’t paying their rent with this. It means they got to at least a hundred paid subscribers. Assuming you set your price to the lowest possible option—fifty bucks a year—you need several hundred paid subscribers to hit minimum wage in the USA.

These are called “bestseller badges” and they stand out from the crowd because most writers aren’t even at this stage. These guys look like the hotshots when in actuality most of them are probably making around a third of what the guy who greets you at the door at Walmart is making. Some of them are probably breaking even on their internet bill with Substack revenue.

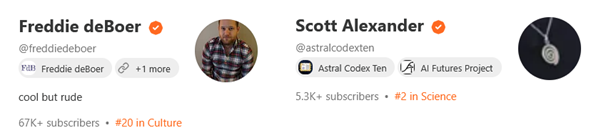

Very, very occasionally the algorithm will show you a rare solid-orange, and these tend to be the people you think of as the stars of the platform—the people who really, actually made it, the internet-famous guys, the book-deal guys, the lifted-brow influencers like deBoer and Alexander.

Solid orange means at least a thousand paid subscriptions, which is—again, assuming the cheapest price—50 grand a year. A lot of these elite writers are still working salary jobs, or else they’re working their ass off on side gigs.

I do suspect that people like deBoer and Alexander are making quite a bit more than this but it’s impossible to tell and rude to ask—solid orange is the largest and most opaque tier to be in. The third tier, the blue checkmark, has at least ten thousand subscribers, and they’re earning more than the combined salary of a couple who are both working full time. As brain surgeons.

So the badge system gives the visual impression that making good money is challenging, yes, but achievable. The reality is that, if the badge ain’t blue, they’re probably still making pocket money.

It’s hard to pin blame for this, though, because…

There’s no model in which everyone gets paid who deserves to

That’s not quite true—there is a model in which everyone gets paid, and it’s called advertising.

I’ve written before about how entertainment companies ditched advertising and now can’t figure out how to pay creatives because the average person cannot afford true cost pricing when it comes to all the entertainment and media that they consume. I used to make good money writing for a free website because the money wasn’t coming out of the audience’s pockets.

Free websites were essentially competing with each other for your time. Our job was to be more important to our audience than clicking on some other website or doomscrolling Twitter. When your income is coming out of your audience’s pocket, you are now competing with every other expense that they have. Now my job is to be more important to you than your Adobe subscription.

This is what Substack writers get really frustrated with and every so often bring up these revenue sharing propositions that will never make sense. “I pay five bucks a month for Rolling Stone and I get tons of daily news from like 40 different writers! Why can’t that work at Substack?” Yeah and Rolling Stone still has a bunch of ads on it.

Slicing a dollar in half doesn’t make two dollars. Substack is pretty much a luxury product being sold as the future of media. If you’re a worthwhile writer the audience is certainly out there, but you have to reach a lot of people, and that’s pretty difficult here because…

You’re advertising almost exclusively to your competition

Not everybody on Notes actually writes longform, in fact a few of my favourite mutual follows either don’t have a Substack publication at all or don’t add to it regularly. That said, the majority of people you’ll encounter organically on the platform itself are other people hocking their own Substacks.

This is partly because the algorithm incentivises it and partly because Substack and its ancillary features are marketed as a writing platform first and anything else a distant second. The only reason it works at all is because writing itself is something that both a lot of people want to do and is very easy to do (not necessarily to do well).

This makes Notes resemble a hobbyist community much more closely than a microblogging platform. When you throw money into the equation it makes things more complicated.

Most platforms in the creator ecosystem now work as kind of self-contained economies (and even the microbloggers like the platform formerly known as Twitter are beginning to explore this) where creators interested in a particular form of entertainment entertain each other and get paid for it, sometimes extremely handsomely. In every notable case that I can think of where the platform is free to use, this income is paid by the platform to the creator from a pool of money generated by something else—once again, this is usually advertising or data collection.

On Substack, you don’t get paid unless someone pays you directly, and the person you’re trying to convince to pay you is the same person who is trying to get paid… by you.

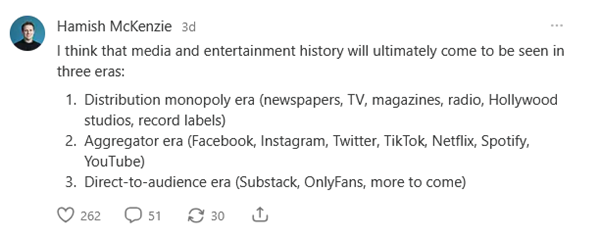

Sabstack’s co-founder Hamish McKenzie recently directly compared Substack to OnlyFans in a way that is very interesting for a completely different reason than he intended.

Imagine if OnlyFans strapped a microblog style social media community to itself and auto-registered everyone who had an OnlyFans creator account, so you basically had a super-horny version of Twitter populated almost exclusively by other pornographers. You would probably get a lot of interesting discussion but not much revenue growth.

The network effect of Notes is great for making friends and sharing your writing for free, but it doesn’t make a lot of sense for getting people to upgrade to a paid subscription. Even though most writers love to read and are maybe even more willing on average to pay to read, at the end of the day you’re still a room full of book salesmen trying to sell books to each other, and everyone in the room has the same goal: To buy fewer books than they sell.

There are only two ways to escape this insularity. One is to leave the room and try to sell to the people outside. On today’s internet this is almost unavoidably going to mean getting really good at social media.

This, by the way, is what every traditional book publisher is going to tell you straight off the bat, even if they’re really interested in your manuscript: Come back when you’ve got 50k Instagram followers and know how to craft a viral tweet.

And that’s basically counter to what is ostensibly the purpose of something like Substack—where you can have your writing seen by people who like to read without having to navigate the burning racist compost inferno that is Twitter. A lot of us actually, like me, are really bad at social media and that is kind of the problem.

So there’s the other way of escaping the insularity, and that is bringing a lot of people from the outside into your bookstore. That’s why…

The whales are the reason anyone sees your work at all

It’s very curious that Substack promotes itself as the thing that’s going to kill and replace legacy media, since much of its success is owed to legacy media. Most of Substack’s biggest stars are superstar journalists who got sick of editorial oversight. They didn’t grow their careers on Substack the way that they tell you it’s supposed to work… they had the clout already. Their milkshake brought all those boys to the yard and not necessarily better than yours, but, you’re damn right, they’re going to charge.

Here's what you need to understand about Substack: Those people are who the Substack platform is for.

The fierce anti-celebrity culture on Notes arises specifically from the backward notion that it’s not for them, and the indie writer immune system of the Substack platform needs to target and eliminate already-popular authors on sight to maintain the playing field. Hence the recent situation with bestselling author Glennon Doyle, whose arrival was met with anger, and whose compliant departure was met with… greater anger, such is the way of angry mobs (how dare you attempt the moral high ground? Come back and take the rest of your beating!)

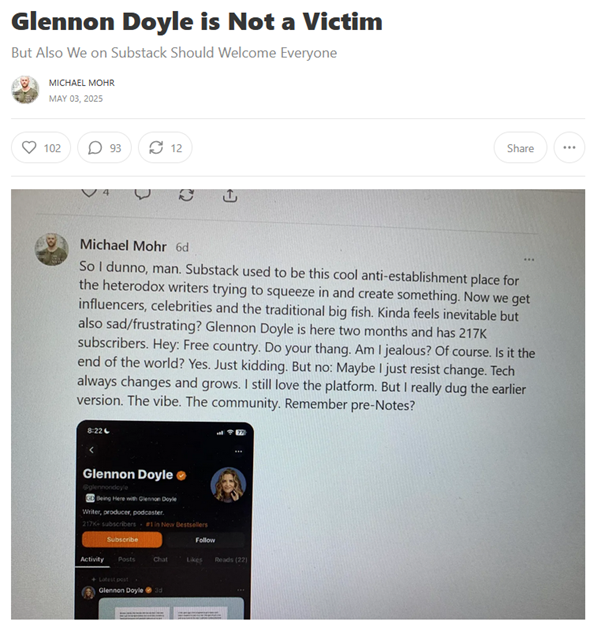

I think a lot of my feeling on this is best articulated as a response I think a lot of my feeling on this is best articulated as a response to this piece by the novelist and separated-at-birth-Bill-Burr-twin Michael Mohr, which is complicated because it’s agreeable in approximately the same number of ways that it is infuriating.

I’m going to admit I flip-flop really hard and frequently about Substack in general—I can really get on the defensive about the shame culture that its users face on platforms like Bluesky, which is largely a bunch of virtue signalling and ladder-pulling. On the other hand, I don’t have a lot of tolerance for pro-Substack sycophancy either, because all of these platforms exist somewhere on the spectrum of evil and we have to deal with this as best we can.

Mohr’s error is common among those who take the Substack Kool-aid by the pint glass, in his words: “Substack started as a place for serious writers generally outside of the mainstream. The ‘heterodox’ writers, one might say.”

For guys like Mohr, “heterodox” is code for “anti-woke.” The notion of Substack as Rumble for writers. He clarifies this by bizarrely listing small-bean lil’ indie darlings you’ve probably never heard of like Bari Weiss and Sam Harris among the protagonists of his anti-celebrity screed.

On the agreeable side, he says people like Doyle should be allowed to use the platform, free speech and all, but (back to disagreeable) it’s unfair that they can come in and just hoover up all the money like they aren’t already famous.

She had, after only eight fucking weeks (and I use the curse word here purposefully) 217K subscribers. You heard me right. Let me repeat that. Eight weeks. TWO HUNDRED AND SEVENTEEN FUCKING THOUSAND SUBSCRIBERS. Lord knows how much money she was no doubt already raking in just for being Glennon Doyle.

I want to note as kind of an aside, across the grain of the anti-bullying kick I’ve been on recently, that it’s interesting that Mohr uses a Stephen King quote here as an appeal to authority to bolster his opinion that “Fuck Doyle; she’s fucking famous, no one kicked her off the platform, and if you’re so hyper-sensitive that you can’t take a little criticism online, then why even write to begin with?”

“If you expect to succeed as a writer, rudeness should be the second-to-least of your concerns. The least of all should be polite society and what it expects. If you intend to write as truthfully as you can, your days as a member of polite society are numbered, anyway.”

Interesting because Stephen King quit Twitter this year. (Yes, he did return eventually, but only tweets a couple of times a month now). His quote, from On Writing, is about how writers need to be able to accept criticism of their writing, even criticism they feel is really unfair.

It’s not about how writers are somehow uniquely obliged to cop truckloads of random abuse hurled at them endlessly and just sit there open-mouthed even if they have the option of leaving the room. I’ll never understand this idea that people who attract hate mobs for any kind of reason need to learn how to Take Their Medicine because hate mobs are a fact of life. It’s like this uniquely American idea that you need to get used to wearing a bulletproof vest to the mall because this is the way things are.

All that aside, the reality is that attracting celebrities to Substack and having most of the money go to them is exactly what Substack is for. It’s not a side-effect, and it is in fact the only mechanism through which most people will ever encounter your writing at all.

Substack isn’t exactly a pyramid scheme, but it’s somewhere in the neighbourhood. It’s in the outer suburbs. The real money that Substack earns, as a company, comes from the blue checkmark class. The whales. The celebrities who brought their entire fanbases into the ecosystem. It’s why Substack’s search tools are so weak and their development is such a low priority beneath simply bringing users in by the bucketload.

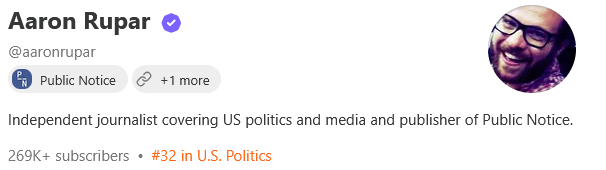

If you click on any given Substack user profile (especially those who aren’t running publications of their own) and look at the list of who they subscribe to, particularly who they’re giving money to (they’re listed at the top and have a little icon on them) you’ll very frequently see things like Matt Taibbi’s Racket News, Bari Weiss’ The Free Press, Jesse Singal’s whatever the hell his is called, or on the left, Aaron Rupar, Zeteo, JoJoFromJerz… The whales, in other words, the ones who are hoovering up all the limited funds that could be going to smaller writers.

But if you look underneath, you’ll usually see a whole bunch of other writers they subscribe to for free… and these are eyeballs that wouldn’t even be available to notice you otherwise.

You’re not going to make a living on Substack. But if you’re savvy, you might be able to take advantage of the people who do.

If you're wondering why, in light of all I've just said, I have payment tiers for my newsletter... support is still support, it's noticed, highly appreciated, and never taken in vain, and you are my bestest best peeps. I feel like those who choose to pay me do deserve something special which is why you get to read my stuff in full a week ahead of everyone else.

But I'm also under no illusion that I'll ever make a living with newsletters, which is why my weekly piece is ultimately free for everyone and I'm hoping to use this as a promotional platform for bigger writing projects... such as this book that I'm writing, which will discuss more about hate mobs on the internet and touches on more of the themes of this article.

The working title is How Geeks Ate the World and I’m going to be dropping parts of the draft into this very newsletter as the project comes along—but only for paid subscribers. So if you want to read along in real time, please consider subscribing. Otherwise I’ll be keeping you in the loop. Check it out here: