The Betrayal of Carl Sagan and the Rebirth of Cecil Rhodes

“To think of these stars that you see overhead at night, these vast worlds which we can never reach. I would annex the planets if I could; I often think of that. It makes me sad to see them so clear and yet so far.” — Cecil Rhodes, from his last will and testament

One of my heroes growing up was Carl Sagan. Like a lot of young boys it was, for a time, space and dinosaurs. I read New Scientist and books by Stephen Hawking, and it was the awe and optimism radiated by Hawking and Sagan, and the respect and admiration they had for the cosmos that drove my imagination.

The scale of space was staggering to me. The way we can only imagine through math what its distant frontiers would look like to our mortal eyes.

What really endeared me to Carl Sagan, though, was his genuine love for humanity. There were only a few people of that era who gave vibes of being pure good, like he never made a single choice in his life that wasn’t the correct choice and you couldn’t find anything to disrespect about him. There was Mr Rogers, and there was Carl Sagan. And they say you should never idolise a human being because even the angels will let you down, but you want to believe just this once.

One of the best things about Sagan was that he loved nature and the cosmos without being in any way misanthropic about it. He knew our species could do better but he was rooting for us completely. While nations and peoples fought each other for dominance and supremacy, Sagan alone humbled us. All of our conflicts and strife, everything that has ever happened to a person or by a person has taken place somewhere on this barely visible pale blue dot.

He rejected anthropocentrism the same as he rejected racism, but he did not reject humanity. He did not see human beings as a plague, just as part of the bigger story.

Sagan promised us that we would one day venture to the stars. Human curiosity and ingenuity would make it inevitable that one day we would outgrow ridiculous imagined difference like racism in the spirit of recognising what makes us the same. We are, he thought, in our infancy, and we were going to make it, and we were going to wade out into that cosmic ocean. He did not live to see it, but I was so excited to imagine that I might.

Then human interest in space travel kind of died off for a couple of generations. We got caught up again in our squabbles and it started to look like we weren’t going to make it after all. But just in the last few years there seems a renewed spark. The interest in exploring beyond our blue dot is starting to reawaken. For the first time in many years, major technological advances have accomplished feats that bring the cosmos back into our reach, and the space program is booting back up, sputtering and coming to life like a long dormant engine.

I can’t muster the excitement I thought I would feel. It just isn’t there. If you know me by now then you know why.

On Sunday the 13th of October, as America entered the final three weeks of a generationally consequential election cycle, citizens of not just the United States but the world paused politics for just a few moments as they witnessed a spectacular milestone in human technological evolution and a miracle of human ingenuity.

Starship, the largest spacecraft ever built, and the first conventional rocket designed to be completely reusable, successfully launched, flew, achieved orbit, and landed intact, with no crew on board. It’s the first major triumph in the new fledgling era of space exploration. The so-called Artemis project, the successor to Apollo, plans to put people back on the moon, and then beyond.

“A still more glorious dawn awaits,” Sagan declared in an episode of his documentary series Cosmos, “Not a sunrise, but a galaxyrise. A morning filled with four hundred billion suns. The dawning of the Milky Way.”

So why am I alone being such a grinch about it, just because the owner of the company that designed and built Starship is Elon Musk?

I could be an adult in the room like Hamish McKenzie, Substack’s co-founder and Chief Writing Officer (a title I think they made up because there can only be one CEO and he didn’t draw that straw), who has been increasingly open in recent weeks about his disdain for the billionaire who crippled Substack by blocking links to it on Twitter and has shown no interest in ever softening his stance despite the olive branches held out by the actual CEO, Chris Best.

McKenzie, who’s been taking pot-shots at Musk for weeks since Musk’s aggressive censorship of Substack journalist Ken Klippenstein, was nevertheless prepared to put politics aside and unreservedly praise Elon Musk for contributions to humanity that dwarf the negative.

Do you, under any circumstances, “gotta hand it to” Elon Musk? Does it betray a lack of maturity that I cannot hold my nose and cheer for this despicable human being’s technological victories and focus on what they can usher in for the rest of us?

And he is a despicable human being, let’s not be bashful about that. A man of incalculable wealth who wields the full and true power of capital as a weapon, not a threat or a shield. God help me I actually prefer the billionaires who hoard wealth and sit in their mansions and yachts, who rob us and then leave us alone.

I’m not a full-throated Marxist. I can forgive banal classism. We all feel greed. What I just can’t look past are the bigotries he holds that surpass classism. On Twitter, he doesn’t just hang out with other oligarchs, with whom he shares little in common but the number of zeroes on his bank statement, but instead banters with low-class, low-status, gutter trash neo-Nazis, with whom he shares quite distressingly more in common.

Elon Musk is regularly compared to Henry Ford for reasons that make a lot of sense if you know anything about Ford’s business accomplishments and make even more sense if you know about his politics.

I don’t think it’s a great comparison beyond the wit of it. A much better and deeper comparison is between Elon Musk and Cecil Rhodes.

Rhodes was a man who liked branding. His name lives on in just about everything you can think of that derives from the word “Rhodes,” from Rhodes Scholarships to the former nation of Rhodesia (stopping short of Rhode Island and War Machine from Marvel Comics). It’s not as abstract as the letter X, but his life was consumed by the insatiable need to shape the world in his image, to burn his name into the Earth’s crust like a cattle brand.

If you read any quotes by Rhodes, or about him, either detracting or praising his life and works, it can be very difficult to discern whether the subject is Rhodes or Elon Musk. Listen to “pro-colonialism” historian Nigel Biggar’s defense of Rhodes and notice how seamlessly it could be applied instead to Musk, from one of his defenders.

The similarities aren’t only superficial but even the superficial ones are spooky. Both men derived their initial fortunes from African precious stone mining—for Rhodes, it was diamonds, as he founded the notorious De Beers company. For Musk, it was emeralds, as his father worked with businessmen who had stakes in Zambian emerald mines. This is a fact that Musk once embraced and then later began to deny as his personal brand changed. Musk, as his politics drift ever rightward and more deranged, is becoming so adept at crafting disinformation as a means of mythmaking that it’s unclear to what extent he even knows what the truth is anymore.

Rhodes’ grandest industrial project, unaccomplished at the time of his death and never realised, was to revolutionise transport by establishing a grand rail line from Africa’s southern tip right up to Cairo. Musk’s hatred of trains notwithstanding it’s nevertheless another remarkable parallel.

What drove Cecil Rhodes was a hunger for expansion, influence, and control that is difficult for us to understand if we don’t share the compulsion and I think can be difficult for historians and biographers to grasp for this same reason. There is such a temptation to rationalise him with philanthropic motives—that his heart was just so big that his empire couldn’t grow fast enough to accommodate it. In reality I think what afflicted Rhodes the same as Musk today is something more similar to the types of hormonal disorders that prevent people from feeling full when they eat. Except, in this case, they’re eating the world.

Rhodes bought up companies and amassed capital, and recycled that capital to buy more companies and amass capital. Fruit farms. Oil fields. He had no single theme except to bring more and more of the wealth of Africa under his exclusive control so that he could decide how best to disperse it for the betterment of his people—white people, foremost.

The white British, he contended, were the world’s most superior people.

In Britain and South Africa Rhodes holds the same kind of precarious historical status as Christopher Columbus does in America—a pioneer with a key role in local history and the mythology of empire, sparsely paralleled record of nation building, and a lot of statues that a lot of people want to rip down. His defenders say that he wasn’t a racist, using the spurious argument that pitying black people isn’t hating them. That his project to uplift the native inhabitants of Africa by removing them from control over their nations and instead bringing them under superior British rule was one of noble charity.

It is much the same argument that defenders of Columbus’ subjugation of the native peoples of America use today, as well as Captain Cook for Australians and any other number of imperial colonial projects.

Once capital had brought him as far as it could alone, Rhodes began to amass political power. He ran for parliament in one of the British colonial nations, Cape Colony, and eventually became its prime minister. He began to craft the legislative and educational reforms that would divide the races and eventually inform Apartheid. The immense super-conglomerate of corporations that Rhodes controlled at this point, which became known as the British South Africa Company, did the next logical thing and just decided to call itself a country, because what’s really the difference between a board of directors and a parliament when you get down to brass tacks?

The name of this new country was a no-brainer—Rhodesia.

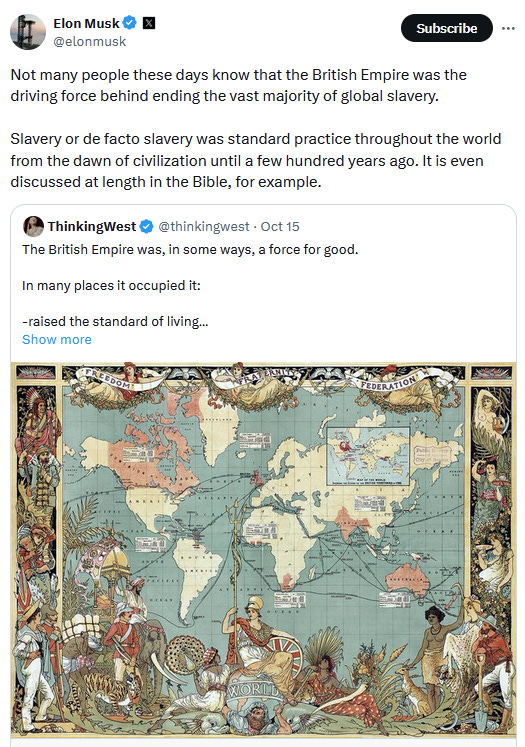

It is kind of fascinating that Musk never mentions Rhodes (ever, as far as I know, at least not publicly) because they are so kindred. Without mentioning Rhodes by name he has nevertheless on multiple occasions expressed grand approval for the British Empire’s activities in Africa, and the conservatorship role it granted itself over black races.

Elon Musk isn’t speedrunning Cecil Rhodes’ life—it’s taking him a lot longer, Rhodes was dead before 50—but he is reenacting it. He is currently at the point at which it’s difficult for him to own more than he does and so he is entering politics. Through his alliance with Donald Trump, he has vowed to enter American government and turn the de facto power of capital into direct tangible power.

And yes, his promise is that his companies will soon call themselves nations and that people will live free under his enlightened rule. The only difference is that the world has been divvied up already and there are no packages of land left for him to plant his flag. No, Space Rhodesia will be on Mars, and as for the diversity of its racial representation—well, given his opinions on black people flying planes let’s say I doubt there will be many of them on these spaceships.

So what, to me, as a man who idolised Carl Sagan and who still does, and in whom the spirit of wonder about exploring the cosmos never died, what does it actually matter that the face behind this renewed human drive is a man I personally despise every bit as much as I loved Sagan?

Especially considering Elon Musk’s prediction record for timescales means he will very likely die (on this planet) before he sees his vision realised, just as Cecil Rhodes never lived to see his grand African railroad?

It’s just… I guess the vibe is different. And the vibe, it turns out, matters.

On the subject of colonising space, or even Mars in particular, Sagan was of mixed feelings. Because he placed human beings no higher or lower in importance than any other phenomena in the cosmos, he saw space exploration as a ritual of humanity’s bonding, coming together as one with each other and with the universe.

No hierarchies. No power struggles. Peace, unity, and respect.

Elon Musk sees space exploration as a mission of colonial conquest. Though the dreams might seem superficially similar there couldn’t be a wider gulf between the attitudes of Elon Musk and Carl Sagan. Musk is strict, regimented, hierarchies all the way down: Himself at the top of the white race; The white race at the top of America; America at the top of humanity; Humanity at the top of living things; Living things at the top of the cosmos. All the universe will fall into line according to this order.

Even if we still get a cool Star Trek future out of this in the end, can you forgive me for being pissed off that this is how we get there? I reject the idea, as many scientists do, of venturing into the stars with a colonial attitude.

In fact, we are at odds from the get-go even if Musk’s vision is similar to mine because I do not agree to his terms. Elon Musk, narcissist that he is in assuming he alone holds the gateway to space, has taken to holding space hostage. He will not take humanity to space, he warns, until the United States elects a far right government. He is two years, he reckons, from launching a fleet of starships to Mars, on the sole condition that Donald Trump is elected president.

Presumably if it’s Kamala he’ll detonate the launch pads or something.

I am, of course, not an American so I can’t vote in this election and this particular condition is beyond any measure of my control, but the philosophy is one that I will spend my life fighting against in any way that I can. I would fight what this stands for even if it means we never get to explore the cosmic ocean. I like to think that Carl Sagan would be proud of me for sticking by my principles, and to be honest with you… I’d still prefer to impress Carl than meet a Martian, if I have to choose.

Also, if Elon Musk does achieve his vision while he’s alive and he does get to build his own Rhodesia… You know what he’s gonna fucking call it, right? You know it, I know it, say it together.

Ugh.

“Planet X.”